Director Chris Brown’s superb documentary “High Ground” follows a team of eleven Iraq and Afghan war veterans and their mountaineer guides in their quest to ascend Mount Lobuche, a 20,000 foot peak in the Himalayas.

The film follows a relatively standard narrative structure, from the first days assembling gear and training in Colorado, through the arrival at and travel within Nepal, to the actual ascent of Lobuche. But interspersed with the travelogue and climbing footage is the film’s true remarkable beating heart, a series of emotionally charged interviews with the veterans, simple and direct, where their own words and stories cut to the core and provide the fabric on which the rest of the film is painted.

They have all been wounded by the war, some physically and visibly, some internally from post-traumatic stress or traumatic brain injury. Their stories are all different in the details, but remarkably similar in that they have been irrevocably changed by the war, and as one veteran says, “can’t be the same person anymore” once they came back home.

The traps of easy sentiment are many in such a subject matter, but are smartly sidestepped here by the straightforward treatment. The filmmakers have brilliantly culled the most poignant and revealing moments out of their interviews with the veterans, and assembled them in a concise, focused fashion. This keeps the story moving forward, yet allows you access to the veterans’ individuality, and to feel connection to what many of the climbers clearly see as a mission as important as anything they did in the war itself. The final ascent carries genuine suspense in the real possibility that some of the climbers will not succeed.

The veterans enter on this mission with many different hopes—to find meaning in a baffling world, to inspire other wounded veterans, to memorialize a fellow lost veteran. Climber Lona Parten is not a veteran, but lost her son in the war, and climbs because her son felt strength and peace in the mountains and she hopes to experience that same peace and connection with him again. Interesting parallels are drawn between mountain climbing and warfare, in their sharing of sudden, life-threatening import and the adrenaline rush of its motion.

Veteran Steve Baskis, who lost his sight in the war, acts as the emotional core of the narrative, and the climax of the films revolves around his ascent. The filmmakers wisely avoid overstating any obvious metaphor of his blindness, and instead choose a series of telling details of his struggle with the terrain and techniques of climbing, and the implied connections to his struggles in the world at large. Another especially memorable figure is “Ike” Isaacson, whose traumatic story of loss and survivor guilt comes at a well-judged point in the narrative and heightens the emotional stakes of the film for viewers.

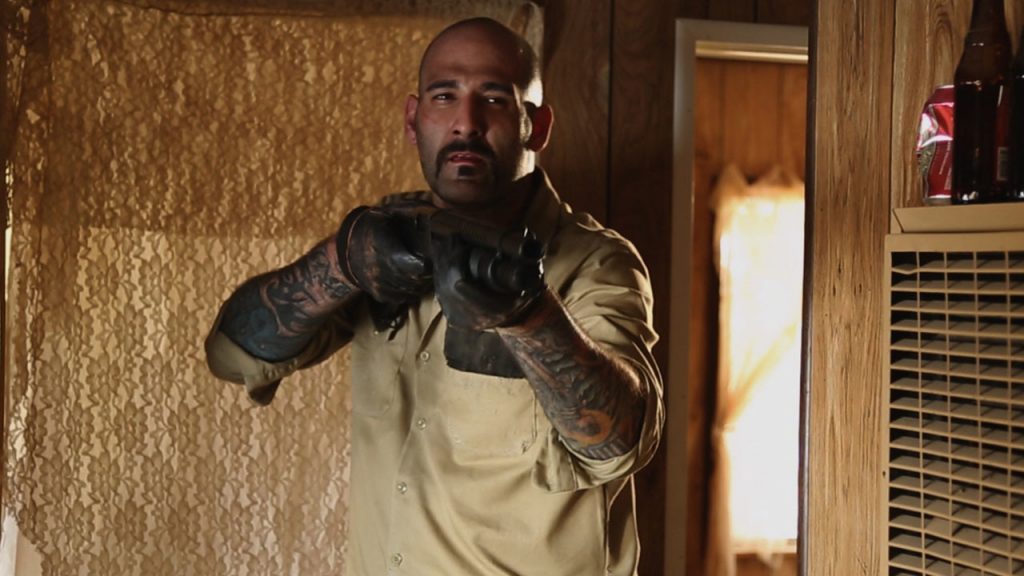

Perhaps the most fascinating figure in the film is imposing veteran Dan Sidles, who suffers from PTSD and whose torso is now covered in a series of vivid tattoos, a kind of visual armor that both repels and attracts the outsiders he simply can’t relate to anymore, but can’t do without either. He speaks with dramatic, cogent lack of affect, and In one of the films most understated and moving moments, he confesses that he thinks he will never have any kind of close relationship again, and that civilian life is just too purposeless to be worthy. His description of the results of building warriors, turning them loose, and then asking them to stand down afterwards is a near perfect summation of the soldiers’ dilemma and challenge.

A short but charged segment in the film, narrated by soldier Matt Nyman, describes in depressing and shocking detail the conditions he endured while at the Veterans Administration Walter Reed Hospital, conditions unworthy of any civilized nation, much less one professing to care about its wounded warriors (Walter Reed would later be shut down completely because of these conditions).

Brown wisely provides moments of relief and humor in what could be an overwhelmingly emotional experience. Veteran and amputee Cody Jukes is a comic relief of sorts, with his easy-going Dude-ish persona. There is eye-catching local color and flavor in the footage from Katmandu and a monastery location, and the vistas of Himalayan peaks and scenery are breath-taking, shot in gorgeous HD detail.

Video:

“High Ground” is shown in widescreen 16.9 format. The DVD transfer is beautifully done, with crisp location footage and gorgeous highlights of texture. The occasional low-light conditions add to the emotional impact, rather than detract.

Audio:

The film has two audio options, a 5.1 surround sound track and a 2.0 stereo track. For this review, I watched the 5.1 track, and the sound is pleasantly clear and clean, given the circumstances of the location filming.

Extras:

Not as comprehensive as one might hope, given the fascinating subject matter, but what is provided is solid and enjoyable.

- a humble, low-key commentary track with director Chris Brown, co-writer and producer Matt Murray, and producer Don Hahn. They provide a great deal of interesting background information about the challenge and personalities of the veterans, the technical and narrative objectives of the film, and the choices involved in assembling the final cut. A rare commentary that informs and expands on your experience of the film.

- two deleted scenes, including an informative tour of the Lobuche base camp, and extended footage of the altitude sickness suffered by veteran Matt Nyman on descent, and the treatment he received.

- theatrical trailer and audience reaction trailer

Parting thoughts:

Beautifully moving in its simplicity and honesty, “High Ground” perceptively explores the always-contemporary issue of the human costs of war, and presents a portrait of the resilient human heart that is unflinching and deeply resonant.