Like many kids of my generation, I loved the original “Little Rascals” comedy shorts—not as much as “The Three Stooges,” but enough to feel some measure of excitement when one of them was rerun on television. But like the “Stooges” shorts, these were hit-and-miss . . . often within the span of those 10-minute films created during the ‘20s and ‘30s.

Like the “Stooges” shorts, “The Little Rascals” installments from Hal Roach Studios were driven by character interaction and antics, with the kind of exaggerated effects and outcomes that would drive TV comedies for many years to come. You’ve seen them on countless shows: oven doors that pry open with monstrous, Blob-like balls of dough after the Rascals added too much yeast; suds that also grow out of control when too much soap is added to the laundry or bath; or Rube Goldberg contraptions that the Rascals were famous for building that almost always misfired—like a dog-washing machine that went loco.

And like the “Stooges” shorts, “The Little Rascals” outings relied on simple tried and true plots that could be recycled and resolved (or not) within a 10-minute span. There were cases of misunderstanding, attempts to raise money, attempts to impress or behave, challenges to one of them, visiting relatives, or various family mini-crises.

When the original short comedies were made and shown in theaters, the Rascals appealed because these were Depression-era kids trying to make it as best they could, whether it was improvising over play or attempting to do the same thing with work. Often they tried to help the adults, and just as often things got messed up. People whose lives seemed to run the same gamut could identify, and the cute factor made them smile. It was the transposition of the adult world onto children’s.

Two decades later, when the Rascals were a fixture on American television, that connection of identification was gone, but “I Like Ike”-era kids and adults living in a world of relative prosperity found it interesting to go back in time and see what it took to live through the Depression. This new generation of viewers was intrigued by the elaborate contraptions that the Rascals would build out of scrap, and charmed by the naive simplicity of the children. Their inventions were ingenious, and they were cute as the Dickens.

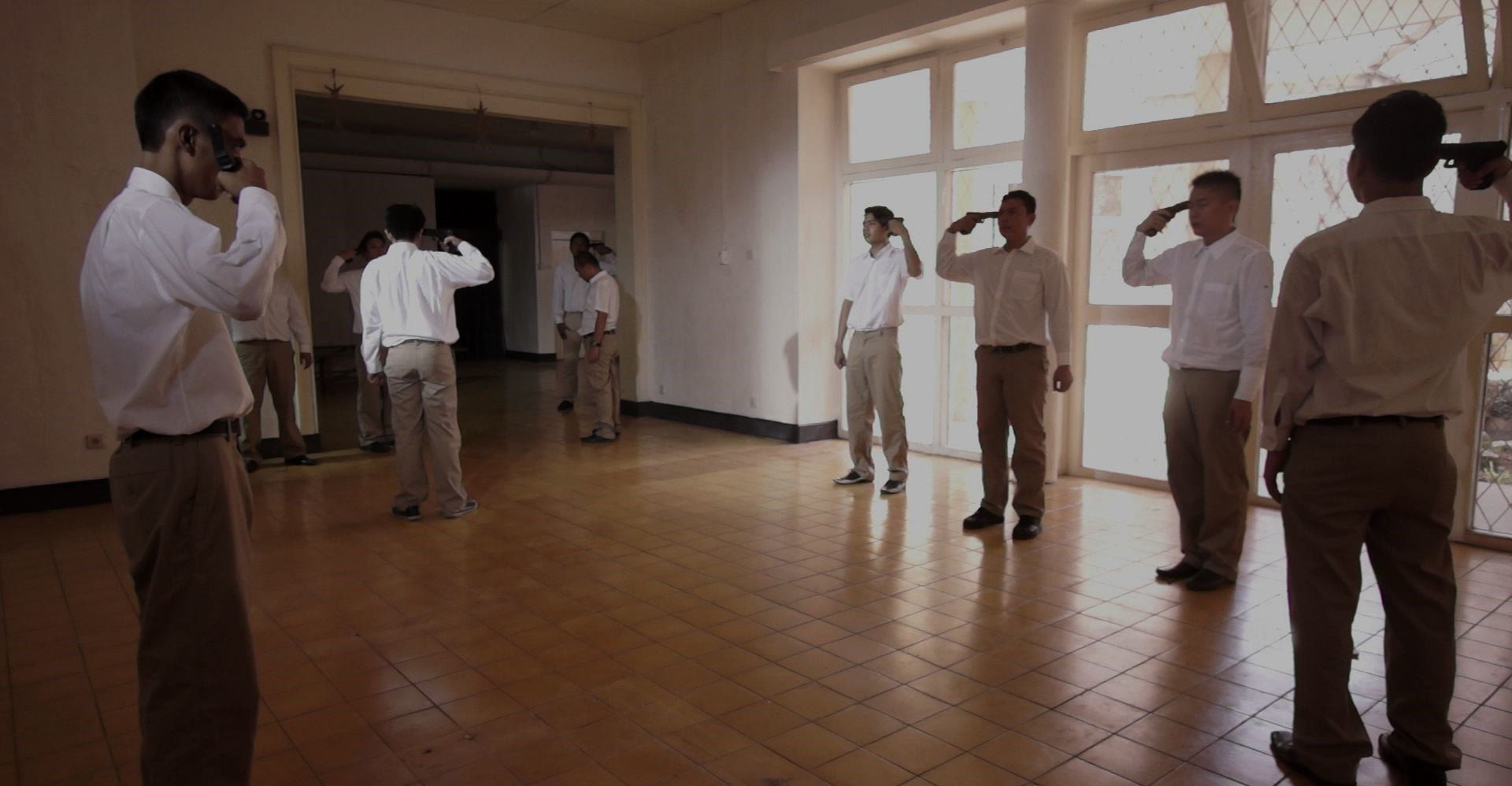

But now kids are into hand-held devices, social networks, gaming, and fast-paced special effects, so I was curious what approach Alex Zamm would take to try to make the Rascals relevant for an even newer and more tech-savvy generation of kids. After all, Universal tried to update “The Little Rascals” in 1994 with only mixed results. Seventy percent of the audience liked it, but only 27 percent of the critics, according to Rottentomatoes.com.

As it turns out, Zamm, whose previous films are mostly sequels (“Inspector Gadget 2,” “Dr. Dolittle: Million Dollar Mutts,” “Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2,” “Tooth Fairy 2”) doesn’t do anything radically different, so it makes sense that at best the audience response to this direct-to-video feature will be once again mixed. Small children might find it funny, but those who remember the Rascals will see hit-or-miss moments that either capture the spirit and characters or miss the mark entirely.

One problem is that the transposition seems to be nearly exact, like a photo of the Rascals dragged onto a modern computer screen that automatically resizes it to fit the space. The simple, familiar plots may have worked in the span of 10 minutes, but when you have 93 minutes to fill it feels utterly deficient. Here, several plots from the old Rascals shorts are cobbled together, with one of them—raise money to save Grandma Larson’s Bakery—the thread that holds the film together.

Strangely, though, Zamm made the decision to mix periods. The Rascals look, dress and talk pretty close to their Depression-era counterparts, but other elements make it seem as if the story is set in the ‘60s, while still others evoke contemporary times. The result is more confusion than the sense of timelessness that the filmmakers were obviously seeking. I much preferred the approach taken with “The Brady Bunch” movies, where the Brady’s were an anachronism in a world that had passed them by. It made more sense than what we get here.

Here, the kids dress as they did during the Depression, while the teacher and other students wear contemporary dress and the teacher has an iPod dock on her desk. The songs are things like “I Got You Babe,” from the ‘60s and ‘70s. Wait, songs? Yes. The kids sing and perform, and the way they plan to save Grandma’s bakery is to win a talent contest. But a lot of viewers may think that Grandma doesn’t deserve her bakery if she has the poor judgment to say to the kids, “Would you watch the bakery for me?” as she leaves them to wreak havoc. Here, rich kid Waldo’s dad (Greg Germann) drives a yellow Hummer, and Waldo drives a smaller customized golf-cart version—never mind that he’s too young to drive a vehicle on the streets. And never mind that we never learn why Grandma’s bakery, with its blend of ‘50s and ‘30s decor, is the only place that Waldo’s dad can build his phallic-shaped super mall.

Even tougher to swallow is the clubhouse. Kids don’t hang out in clubhouses these days. In the Depression the Rascals had a ramshackle place built out of wood scraps, cardboard, and anything they could find. Here, it’s like they called “Treehouse Masters” to build a “shack” treehouse on the same lot as Grandma’s bakery that even has a stained glass window in the front door . . . and hub caps hanging on the outside like decoration. The two elements don’t go together, but they do illustrate the strange vibe that “The Little Rascals Save the Day” gives off.

The kids try hard to ape their predecessors, but do so with mixed results. Spanky (Jet Jurgensmeyer) isn’t nearly as portly or adult-looking as the original, but at least half the time he gets Spanky’s way of speaking down pat. The other half? About like the other characters, who don’t even come close—with the exception of Eden Wood, who plays Darla. She not only looks the part, but also acts the part and manages to update the character in believable ways. But where’s Froggie? Why isn’t Alfalfa’s voice crackling as much? And what’s with the palm trees? Weren’t the Rascals supposed to be in New York? The most “rascally” this film gets is when the kids crank up their pet-spa, which will bring smiles and remind fans of the original short that spawned it.

If you’re into comparisons, though, you’ll lament that the dog comes the closes to the real thing. And if you’re into logic, humor, and some measure of complexity, you’ll also find “The Little Rascals Save the Day” lacking. This one is only for smaller children, who may be able to look past the film’s shortcomings and enjoy the antics simply because the focal point is a group of children acting independently of adults.

“The Little Rascals Save the Day” has a runtime of 98 minutes and is rated PG for “some mild rude humor.”

Video:

“The Little Rascals Saves the Day” looks great on Blu-ray, presented in 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen and with a near-flawless AVC/MPEG-4 transfer. Aside from minor ghosting in several instances this retro comedy is a visual treat, with realistic skin tones, nicely saturated colors, and decent black levels. Inside Grandma’s bakery draws attention to how detailed everything is, and how there’s a suggestion of depth as well.

Audio:

The featured audio is an English DTS-HD 5.1, with additional options in Spanish and French DTS 5.1 and subtitles in English SDH, French, and Spanish. Everything is clear as a bell, and even the mid-tones have a sparkling presence.

Extras:

This combo pack includes a DVD of the film and a UV copy. But there isn’t much in the way of special features—only a few deleted scenes, a gag reel, and “animatics.”

Bottom line:

A marquee reference to Hal Roach isn’t enough to bring Roach’s Rascals into the 21st century, and little that director Alex Zamm does is enough to help these Depression-era cuties make the transition into contemporary comedy. Is it an improvement over the 1994 live-action film? Yes. But that’s not saying much.