Like Pecos Bill or Paul Bunyan, some films just keep growing until they acquire legendary status. “Body Heat” is one such film. So is “Sex, Lies, and Videotape,” an indie that launched Steven Soderbergh’s career and set Cannes on fire, winning the Palm d’Or and also snagging the Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival. Soderbergh even received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay. And the sexy title certainly didn’t hurt.

It’s a proficient film, but I’m not sure that it deserves its iconic status, unless you think of it as the Curt Flood of independent filmmaking. Flood was the center fielder for the Cardinals who refused to accept a trade, and it was his stand that led to a new era in baseball. In a way, “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” did the same thing for indie filmmaking. People suddenly started looking and indie films differently. They were soon after considered viable entertainment that could rival big-studio offerings, rather than just self-indulgent or esoteric exercises in filmmaking that were destined for art houses and nothing more.

“Sex, Lies, and Videotape” was a breakout film for Andie MacDowell, too, who’d previously only done “Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes,” and, like the “can’t stand ’em” actress in “Singin’ in the Rain,” had to suffer the indignity of having her voice dubbed . . . in her case, with Glenn Close’s. In “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” MacDowell earns respect playing a sexually repressed wife who’s in therapy–though probably everyone else in the film ought to be.

Soderbergh, who wrote the screenplay, knows people and he knows sexual dynamics. As a result, “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” could pass for a clinical study, albeit a voyeuristic one. And even that shows Soderbergh’s savvy when it comes to understanding human nature. The whole film appeals to a collectively repressed voyeuristic side that Soderbergh trusts viewers have. And it presents a little morality play that begs audiences to identify with one character or another, then asks them to reconsider. So who is to blame? The distant wife, Ann, who tells her therapist that she thinks sex is overrated and has never initiated physical contact with her husband (with whom she’s had no relations for a long time,) or the smarmy husband, John (Peter Gallagher), who has a tendency to lie and cheat . . . not just with any woman, but with his wife’s sister, for cryin’ out loud. Was she picking up on his vibes? His deceitful personality? Or did she drive him to do what he did/does? And what about her sister, the free-spirited Cynthia (Laura San Giacomo), who tends bar and seems driven to make up for her sister’s lost (sexual) time. There’s a sibling thing going on here, but just as they make an effort to stay friends despite huge differences, viewers are asked to not judge either of them too quickly. Who’s the actor and who’s the reactor? And with whom does Soderbergh want us to side? That’s not always clear, and it’s one main reason why this film succeeds.

Then, just like Ray Bradbury’s “Something Wicked This Way Comes,” along comes an old college buddy of John’s whom he hasn’t seen for nine years, and John invites him to stay at the house without consulting his wife, who now has another thing to talk about in therapy with her shrink (Ron Vawter). Graham (James Spader) is an artsy fellow, and so of course he appeals to Cynthia, who paints. But he seems infinitely more sensitive, perceptive, and honest than John, and so that also makes him appealing to Ann. Yes, you can see this coming, but Soderbergh handles the sexual tension in an interesting way. Despite the title, there’s no nudity, and it’s only suggested that anyone ever has sex-profanity, that’s another story. But as a result, the tension builds and continues to build, with anticipation that promises to lead to something more, always more. That tension is stoked by Soderbergh’s decision to go with silence in the background throughout most of the film, and it really is deafening at times.

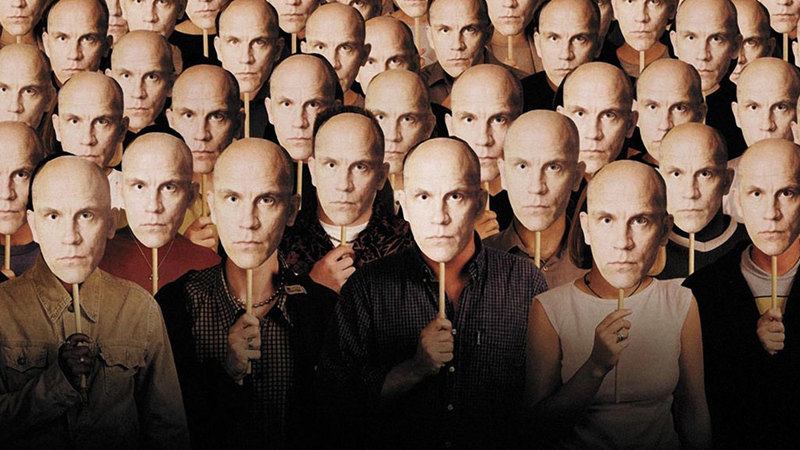

At the center of this “foursome” narrative is Graham’s own sexual fetish: for whatever reason, he can only get off by taping women talking about sex, then later masturbating while he watches. Kinky? You bet. But lest we take any of this too seriously, Soderbergh throws a barfly (Steven Brill) into the mix for comic relief, just to remind us that sexual politics can be as funny as they are sad. In keeping with the voyeuristic theme, Soderbergh gives us a rough-looking film that milks real-time for all it’s worth. But “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” is a slow-moving film, made more so because we can see things coming. It’s like watching a train wreck in slow-motion, knowing what’s around the bend . . . or rather, what couldbe around the bend. It’s the potential for things to happen that ultimately drives the film–that, and questions of morality and blame that both invite and defy speculation.

Video:

“Sex, Lies, and Videotape” takes its cue from the rough, hand-held camcorder footage that Graham shoots of the women in this film. There’s more grain than Blu-rays usually deliver, and a little atmospheric noise. Soderbergh seems content to go with the gritty, because this was always a guerilla-style film with low-budget-looking production values, and a Blu-ray is only going to be as good as its source materials. I can tell you this, though. “Sex, Lies, and Videotapes” looks as good now as it ever has, and Soderbergh reportedly approved the AVC/MPEG-4 transfer himself. Where Hi-Def makes a difference is in the sense of 3-dimensionality that we get. The scene that demonstrates it most convincingly is when we get a character in the foreground, middle distance, and background, all in the same frame/shot, and the sense of depth is striking. Flesh tones are natural looking but not all that rich, while the rest of the colors also tend toward the muted rather than the fully-saturated, and black levels tend to run a little light for my taste. But a sense of visual reality dominates because of that 3-D effect. “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” is presented in 1.85:1 aspect ratio.

Audio:

The audio is rougher still, varying at different times from reasonably clear to muffled, mayonnaise-jar dialogue or dialogue that offers characters speaking who seem to be wearing mikes while others aren’t. One scene especially comes to mind in which John sits at a table and from a quasi-aerial shot we watch him talking with Ann, who busys herself in the background and goes into another room and back again. John’s voice sounds muffled, but Ann’s sounds even more so. And it’s not the only scene that throws a blanket over dialogue. In some scenes there’s a feedback hum in the background, as well.

Music and ambient sound is deliberately limited in this film, obviously to heighten tension. There’s something about a stark sonic landscape in which voices are the only sound that makes whatever discomfort in a scene seem exacerbated. I have to say, though, that it seems jarring when at the apparent fulcrum of the film Soderbergh finally opts for music. My head all but snapped when Ann has her revelation or moment of determination and then struts her stuff past graffiti-painted walls to the bar where her sister works.

For the most part, the sound is center-speaker bound, with the front mains leaning in so close you’d think someone asked them to pose for a picture with the center speaker.

Extras:

Considering this film’s legendary status (however inflated), it’s still surprising that Sony and Soderbergh didn’t come up with more bonus features. Aside from BD-Live functionality, MovieIQ (with its “up to date” pop-up details about the film), and a commentary track with Soderbergh and fellow director Neil Labute (“Nurse Betty”) in which they talk about the film and indie filmmaking, the only bonus features are a handful of diversions. “Steven Soderbergh on ‘Sex, Lies, and Videotape’ runs under 10 minutes and offers more of the same thing we got on the commentary track, and then there are five features that run under four minutes each.

Of those, the deleted scene (3 min.) with optional commentary might spark the most interest among fans, but the “20 Year Reunion at the Sundance Film Festival” is a nice (albeit under five-minute) way to see what the stars are up to now and also revisit the film in perspective/retrospective. Rounding out the bonus features are a couple of trailers.

Bottom Line:

Solid performances and Soderbergh’s sense of human nature and cinematic tension are what hold the “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” together. It’s the kind of film that would-be cinephiles should see at least once in their lives to see what all the fuss is about. But apart from indie filmmakers wanting to dissect each scene to see how Soderbergh does it, I don’t see a lot of repeat plays . . . at least not for casual viewers.