Note: In the following joint Blu-ray review, Yunda Eddie Feng joins John in commenting on the film, with John also writing up the Video, Audio, Extras, and Parting Thoughts.

“The fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” –Shakespeare

The Film According to John:

Alfred Hitchcock directed the 1945 psychological thriller “Spellbound,” so it’s got that going for it. It features a fascinating surreal segment designed by surrealist painter and illustrator Salvador Dali, so it’s got that, too. But most of all it’s got an Oscar-winning musical score by Miklos Rozsa that has continued to bewitch listeners to this day. What the film lacks is much credibility in the plot and character departments, despite the charisma of its stars, Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck. On balance, the direction, set design, and music win out, but that doesn’t make “Spellbound” vintage Hitchcock.

Apparently, “Spellbound” was among the first Hollywood films to take psychiatry seriously, presenting it as the practice of diagnosing and treating mental disorders that we know and take for granted today. However, in 1945 it was still an emerging science, so “Spellbound” gave it some validity and respectability. Producer David O. Selznick, who was in analysis himself at the time, insisted the picture be as realistic as possible on the subject, and the attention to detail proved mostly a success (even if Hitchcock still considered it “only a movie,” referring to it as “just another manhunt wrapped up in pseudo-psychoanalysis”).

Anyway, the real question is how it holds up these days as an entertaining motion picture, and there opinions differ. I’ve watched it maybe three or four times in the past few decades, and while this Blu-ray presentation is the best I’ve ever seen it from an audiovisual standpoint, I still can’t get my mind around the story and characters. In fact, I almost fell asleep about halfway through this time around.

The script, loosely adapted by celebrated novelist and screenwriter Ben Hecht (“The Front Page,” “Scarface,” “Gunga Din,” “Wurthering Heights,” “A Farewell to Arms”) from the book “The House of Dr. Edwardes” by Frances Beeding, seems far-fetched and by the end of the film contrived, even by Hitchcock’s often eccentric standards. Yet there is no hint of humor in this story, peculiar or otherwise; everyone faces things in dead earnest.

The plot involves the arrival of a new doctor of psychiatry, Anthony Edwardes (Peck), at the Green Manors mental hospital. He is there is take over as the head of the facility, replacing the retiring Dr. Murchison (Leo G. Carroll). Among the staff at Green Manors is Dr. Constance Petersen (Bergman), a rather cold, emotionally distant woman who, it appears, has never known love in her life nor ever cares to. However, the moment she and Edwardes see each other, it’s love at first sight. They are in each other’s arms by nightfall the day he arrives. Go figure.

Things would seem to be going swimmingly, at least for most of a day, until Petersen begins to suspect that Edwardes is not all he appears to be; indeed, he may not even be Dr. Edwardes! Every time Edwardes, or whomever he is, sees patterns of lines against a white background, he goes a little nuts, having bad memories, getting dizzy, and falling into fainting spells. As the possibly pseudo Dr. Edwardes grows ever weirder, Dr. Petersen becomes more convinced he isn’t who he says he is. By a few minutes into the film, Peck’s character admits he isn’t Edwardes, that he actually murdered the man, and that he can’t remember who he really is. From there, Dr. Petersen spends the rest of the movie trying to psychoanalyze her amnesic lover, bring him back to reality, and prove his innocence. That can be a long haul.

On the positive side, we’ve got some suspenseful moments involved, as we would expect from Hitchcock, especially ones involving a straight razor and another one involving a revolver. Heck, Hitch even makes a note lying on the floor an object of suspense. He’s also good with trains, and it’s a pleasure seeing the characters riding or about to ride a train at least three different times in the film. Remember “The 39 Steps,” “Strangers on a Train,” “North by Northwest,” and probably half a dozen other Hitchcock films that featured train rides? And, naturally, there are always the artfully shot frames by the master director, the eerily wonderful musical score by Mr. Rozsa, and the bizarre dream-sequence sets by painter Dali to consider, which go a long way toward making us at least remember the film.

On the negative side, the movie unaccountably opens with a lengthy overture and ends with exit music, pretentious touches no doubt instigated by Selznick to give the movie more prestige, as though it were an epic or something. Then, there are Bergman and Peck, both fine actors but somewhat miscast in the roles. Peck was one of those actors who got better (and better- looking) as he grew older, but here looks and acts all gangly, youthful bones; Bergman, on the other hand, always looked great yet doesn’t really fit the part of the frigid psychoanalyst nor make the instant transition to lovesick kitten too believable.

The love affair, though, is no doubt the film’s biggest stumbling block. The icy Dr. Petersen is so head-over-heels, she won’t report Peck’s character to the police after he’s admitted murdering a man? She’d rather follow him to the ends of the Earth to prove his innocence? All this after knowing each other for a few hours? She says “It has nothing to do with love,” as she falls into his arms. Worse, even if we accept that they instantly fall in love, the actors never fully persuade us to believe they’re really doctors or really in love. The fact is, the love affair between Bergman’s character and Peck’s is not exactly a chemistry made in heaven.

John’s film rating: 6/10

The Film According to Eddie:

Made in 1945, “Spellbound” stars Ingrid Bergman as Dr. Constance Petersen, a psychoanalyst. Her boss, Dr. Murchison, has been forced to retire. Therefore, the famous Dr. Edwardes (Gregory Peck) comes to replace Murchison. However, Constance soon finds out that Edwardes isn’t really who he says he is. Rather, he is a victim of amnesia suffering from a guilt complex. Constance decides to help this mystery man figure out his identity.

Given the caliber of its leading man and lady, I was disappointed by “Spellbound” when I first saw it. I felt that the script stretched credulity a few too many times. Most of the film plays as a mystery as Constance and J.B. (the initials of Peck’s character) race to piece together the chain of events that lead to J.B.’s condition before the police lock him away in jail. However, the filmmakers also stuck a love story into the narrative, and this is the single most unbelievable aspect of the film–it bothered me the whole time that I was watching it. “Spellbound” is based on the novel “The House of Dr. Edwardes” by Francis Bleeding. If the love story was in the source novel, then the screenwriter should’ve thrown it out the window. If the love story was not in the novel, then the filmmakers must’ve added it as part of a ploy to sell more tickets to people who wanted to see two attractive actors get touchy-feely on the big screen.

Since I knew what to expect, I was better able to appreciate what “Spellbound” accomplishes while watching the film again. Rather than hoping to see kinetic thriller, I accepted “Spellbound” for what it is–a character study of people behaving in ways that contradict their natural impulses. The leaps of faith required of a viewer to accept that the movie “works” were much smaller this time around than when I first saw the movie almost a year ago. The slyness of Hitchcock’s direction made me smile knowingly a few times, too.

Gregory Peck always manages to impart a sense of intellectual turmoil, even when he’s playing an amnesiac as he does here. Still, since he essentially plays a blank cipher for most of the movie, his character’s resonance with the audience stems for Peck’s ability to generate chemistry with Ingrid Bergman. You can sense the connection between the two, and old-fashioned star power can make almost any situation plausible.

I noted in my reviews of the “Notorious” DVDs about how ravishing Ingrid Bergman looks in that movie. In “Spellbound”, she plays a professional woman (a doctor), so she plays less to the camera (and to the audience) in “Spellbound” than in “Notorious”. However, it is interesting to see the “Hollywood” style of filmmaking at work. In “Notorious,” because of her character’s sexuality, the lighting on Bergman seems muted and dark in nature, as if to paint her as a purveyor of forbidden wares. Here, in “Spellbound,” the light is rather intense on Bergman’s face, especially her already-sparkling eyes. There is no doubt that she plays one of the “good guys” in this film, and the filmmakers never miss an opportunity to tell you so.

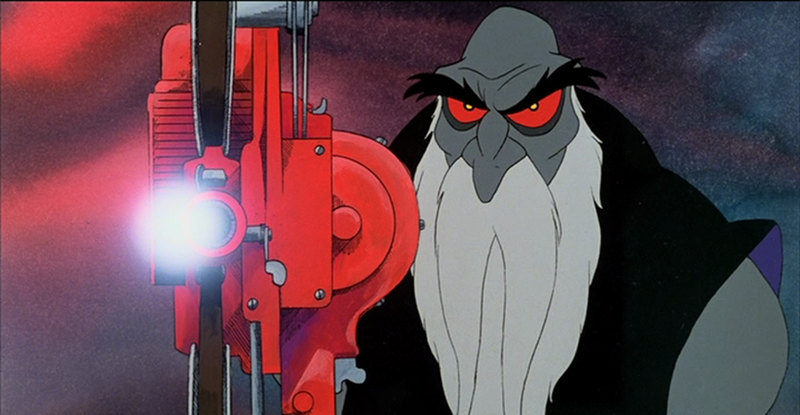

“Spellbound” is probably most famous for the dream sequence designed by surrealist Salvador Dalí, the Spanish artist most famous for his painting of melting clocks. It’s a notable and historical collaboration between good ol’ Hitch and Dalí, especially considering the fact that the film explores the analyzing of abstract dreams. No one took more delight in scaring us with abstractions than Hitchcock (in the “Psycho” shower scene, we’re never shown the knife actually touching Janet Leigh’s skin), and no one took more delight in the absurdities of reality than Dalí. Their collaborative effort in devising physical manifestations of J.B.’s skewed memories provides a look at the way our own minds work.

I still think that “Spellbound” is one of Hitchcock’s less accessible works. It certainly was hard for me to accept that a professional doctor would fall madly in love with a man she hardly knows and who might be a dangerous killer, and some of the narrative elements exist simply to shove the story from one moment to the next. However, there are a couple of great performances in the film, including a charming supporting turn by the gentleman who plays Constance’s mentor. For those of you wanting to move beyond the usual cable showings of “Psycho,” “Rear Window,” and “North by Northwest,” “Spellbound” is a good place to start when looking for a “different” Hitchcock.

Eddie’s film rating: 7/10

Trivia notes, thanks to John Eastman, “Retakes” (Ballantine Books, New York, 1989): “With this film emerged Alfred Hitchcock’s favorite theme of guilt overshadowing and preventing love. Psychoanalysis was faddish in Hollywood at the time; Hitchcock and producer David O. Selznick were probably the first filmmakers to consider it a fit topic for a picture. Ingrid Bergman initially refused her role because she didn’t find the love story convincing. Playing opposite a younger man for the first time her career (she was only a year older than Gregory Peck) disturbed Bergman, as did Hitchcock’s iciness toward actors. Hitchcock didn’t feel that Peck was right for the part of the amnesiac, but he finally had little to say about this casting choice. While rejoicing over the access to Bergman’s audience he would gain in this film, Peck judged his own performance as ‘lousy.’ Most of artist Salvador Dali’s dream-sequence footage was cut from the final version as too distracting. The director performed his cameo as a man emerging from a crowded elevator carrying a violin case.”

Video:

Using an MPEG-4/AVC codec and a high bit rate on a dual-layer BD50, the Fox/MGM video engineers captured what looks probably pretty close to a cleaned-up original print of the film. The 1.33:1 ratio image is clean, with fairly good definition and detail; the black-and-white contrasts show up with a vivid intensity in most scenes; and what grain we see is light and obviously inherent to the film itself. No complaints; it looks good.

Audio:

The sound is monaural, of course, but it’s quite good monaural, reproduced with lossless DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0. There is a slight background noise, barely audible at normal listening levels, and that’s about the only adverse thing one can say about the sound beyond the obvious: There is little in the way of frequency extremes north or south of the midrange, and there is a limited dynamic range. The mids are quite smooth, though, and overall clarity is excellent.

Extras:

There is a healthy set of extras involved, starting with an audio commentary by author and film professor Thomas Schatz and film professor Charles Ramirez Berg, who serve up a good helping of information and trivia while not taking themselves or the film too seriously. Next are three featurettes: The first is “Dreaming with Scissors: Hitchcock, Surrealism and Salvador Dali,” twenty minutes on exactly what the title suggests; the second is “Guilt by Association: Psychoanalyzing Spellbound,” nineteen minutes on the psychological elements in the story; and the third is “A Cinderella Story: Rhonda Fleming,” ten minutes, narrated by Ms. Fleming herself.

The primary extras wind down with a one-hour 1948 Lux Radio Theatre dramatization of the story starring Joseph Cotten and Valli; and a fifteen-minute audio interview with Hitchcock conducted by filmmaker and writer Peter Bogdanovich.

The extras wrap with twenty-eight scene selections; an original theatrical trailer; English as the only spoken language; and English captions for the hearing impaired.

Parting Thoughts:

“Spellbound” may not be one of Hitchcock’s top-rank pictures, but even second-tier Hitchcock is better than what most other directors produce. Although I liked the movie a little less well than Eddie did, I’m going with his rating below since he got to the film first.