H.G. Wells’s vision of a future radically transformed by technology has proven accurate enough; he simply missed on the scale. Wells dreamed of gigantic machines that enabled heroic achievements; massive gyroscopes, fat conveyor belts, and even a great honking space gun to shoot explorers to the moon. He never imagined our 21st century gadgets would be so tiny; pocket-sized streaming devices for a population more interested in gazing at navels than at stars, micro-technology employed to train the perfectly pliant consumer to look down, not up.

Wells was proffering a roadmap more than a prediction; this was the way the future shouldplay out. His lack of ambivalence about his scientific utopia does not prevent it from being terrifying as well as inspiring. In his century-spanning tale, humanity (represented by the very-Anglo urban space of Everytown) has built a squabbling nationalistic society so fatally flawed it must be burned to its foundations by a forever war and a debilitating plague (The Wandering Sickness) before it can be reconfigured by a world council of elite scientists and engineers into something approaching perfection.

If the residents of Everytown are virtually wiped out by unidentified enemy bombers in 1940 and then oppressed by a petty warlord in 1970, it’s just an awkward stage on the path to adulthood, paradise circa 2036. In the shiny new Everytown of one hundred years hence, technocrats rule benevolently, even tolerating the interference of pesky artists and other Luddites who wish to do silly things like impede scientific progress. An unconvincing vision perhaps, but one that was pure H.G. Wells.

It’s hard to picture a studio today giving such total control of a mega-budget blockbuster to a novelist with so little previous film experience, but producer Alexander Korda was smart enough both to realize the marketability of Wells’s name and to recognize the futility of battling the willful author. Wells, nearly 70 when “Things to Come” (1936) was released, was a superstar who had become a widely respected public intellectual. If he was never quite able to shed the label of “science-fiction writer” from his earliest published years, he had long since expanded his scope and was making his name with lengthy futurist speculations that read more like non-fiction than escapist fare. “The Shape of Things to Come” (published in 1933) was styled as a futuristic history text written by a 22nd century diplomat. The framing device was dropped for the film, but Wells maintained total control over the screenplay, even securing a contractual guarantee that not a word could be changed.

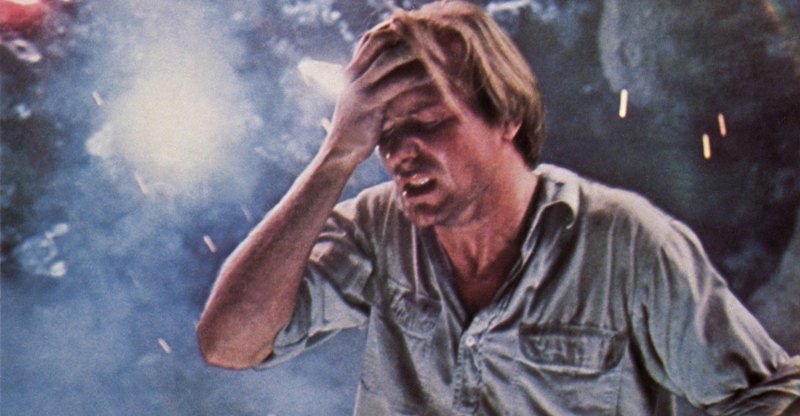

Perhaps Korda and director William Cameron Menzies didn’t mind. They could just point the finger of blame at Wells when star Raymond Massey utters words like “Why has it come to this? God, why do we have to murder each other?” Massey wasn’t too pleased about many of his lines either, but he was always game. And if anyone pointed out just how sterile and boring the ultra-rational perfect future world looked like, well, that’s just how H.G. rolls.

Menzies, better known as a production designer than a director (he had previously worked on the 1924 “Thief of Baghdad” and later helped design “Gone With the Wind”), could take credit instead for the spectacular look of this sprawling epic, though credit would have to be shared with an army of designers from Vincent Korda to Wells’s son Frank (that was in the contract too) and an array of artists brought aboard (and sometimes summarily dismissed by Wells) at various points.

It’s amazing how much better special effects could look three-quarters of a century before CG plunged movies into a gaudy, weightless misery. Shots of sleekly-uniformed aviators parachuting into Everytown, the extended machinery montage that bridges us to a 21st century city carved from the inside of a hill, and that great honking space gun are as awe-inspiring now as the day the film was released. The movie’s depiction of post-apocalyptic society has been imitated time and again; think proto-Mad Max (by way of Flash Gordon) with Ralph Richardson as Tina Turner. The full orchestral score by Arthur Bliss is such a perfect complement to the stunning sets and effects that nobody should mind the moments where the swelling music comes close to bludgeoning the audience.

The century-long trip is such a treat for the senses, “Things to Come” is not undone by its disturbing and naive faith in technological progress. Though Wells surely didn’t intend it, the modern viewer can blaze his or her own path through the final act, choosing to side with the “villainous” Cedric Hardwicke as he leads a revolt against Massey and the other ruling elites: down with progress! You can easily be forgiven for not being able to pick any side in this lily white, unabashedly patriarchal version of Utopia. I am far more inclined to shudder than to rejoice when Massey fires the great honking space gun and speechifies, “Conquest after conquest… All the universe or nothingness!” Whatever the case, there is one indisputably optimistic feature of this now not-too-distant future: no tattoos.

“Things to Come” was not a complete failure at the box office, but it did not recoup its massive budget. Today maybe it would have broken even in ancillary markets. The commercial disappointment helped put studios off expensive, serious science fiction epics for decades and drove Wells out of the film business. But even with all its rough patches and literal-minded didacticism, “Things to Come” is a difficult experience to shake, even more resonant nearly eighty years later as it feels so much part and parcel of a hundred other movies we’ve grown up with. Wells had big dreams. So did Korda and Menzies. And they’re all right there on the screen for us to see so we can dream big too. Just don’t watch it on your iPad, OK?

Video:

The film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. There is a heavy but not completely consistent grain evident throughout which suggests a greater-than-usual amount of boosting was employed. As a result there are several scenes where detail is not as sharp as we’re used to with most Criterion 1080p upgrades. The black-and-white contrast is also not particularly sharp, so some elements blend together just a bit. However, the thick grain is rather pleasing to the eye, making the film feel even older and more mythic than its 75+ years.

Audio:

The linear PCM mono track sounds rather hollow, but I imagine that’s attributable to the source. The main task is preserving the resonance of Arthur Bliss’s full-tilt orchestral score and on that front the audio mix is mostly a success. Optional English subtitles support the English audio.

Extras:

The film is accompanied by a commentary track by film historian David Kalat. I’ve sampled the first 15 minutes and last 15 minutes, and it sounds as if Kalat progresses from an initial focus on H.G. Wells to a broader discussion of the film’s production and the many artistic voices that were able to squeeze in a word or two over Wells’s roar.

Cultural historian Christopher Frayling contributes a newly recorder interview (2013, 23 min.) about the film’s design, including mention of artists whose work did not survive Wells’s scrutiny, among them the legendary Fernand Leger. Wells issued a series of dictatorial memos to the production team, among them an admonition to do the opposite of whatever Fritz Lang did on “Metropolis.”

Historian Bruce Eder discusses the score (2013, 16 min.) by Arthur Bliss, arguing that it was unusually assaultive for its time, a heavy orchestral arrangement that really made an impact on audiences.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy was a Bahaus artist who worked as a production designer on the film. Most of his work was discarded, but elements survive in the lengthy machinery montage in the film. Criterion has included four minutes of unused effects footage that was discovered in 1975. They have also included a 2012 video installation piece by artist Jan Tichy which re-arranges this lost footage in a split-screen format. This piece is titled “Things to Come, 1936-2012” and runs 2 min, 30 seconds.

The plague that ravages the war-torn landscape in the film is described as The Wandering Sickness. Criterion offers an audio recording from a 78 rpm one-sided record of a dramatic reading of the “Sickness” passage from Wells’s novel. 4 min.

The 20-page insert booklet includes an essay by critic Geoffrey O’Brien.

Film Value:

“Things to Come” is hardly an unqualified success, but its ambition is as evident now as it was in 1936. Even with its numerous rough patches and my own burgeoning technophobia, I have tremendous affection for this epic. I hope you will too.